Group Decision Group influence and information cascade

We have two urns, A and B, with Urn A containing 2 blue balls and 1 red ball, and Urn B containing 1 blue ball and 2 red balls.

The following experiment is conducted to a group of people.

We randomly select a urn, and let participants guess which urn (A or B) it is without seeing inside the urn.

Scenario I: One by one, each participant draw a ball from the urn, check the color without showing to other participants, guess which urn it is, and put the ball back to the urn.

Scenario II: One by one, each participant draw a ball from the urn, check the color, but this time show it to other participants, guess which urn it is, and put the ball back to the urn.

So, the question to answer are:

Which scenario leads to more accurate individual predictions?

Which scenario leads to more accurate combined predictions?

It is meaningless if those participants make random decisions. So we assume them to make rational decisions and their decision follow the optimal Bayes decision rule:

Generally, let $\Omega={\omega_1, \omega_2}$ be the set of the states, and $\overrightarrow{x}$ be the vector of the observations, then the Bayes’ decision rule decides $\omega_1$ if , and decides $\omega_2$ if .

Scenario I:

In the first scenario, the information of the decisions made from the predecessors of the current participant are withheld from the current participant.

Individual Decision:

The optimal decision process for each participant is the following: Each participant will decide the ball is from urn , if she draws a black ball; and will decide the ball is from urn , if she draws a white one. This is supported by the following proof of Bayes’ Theorem and Bayes’ decision rule: The posterior probability of the ball is from urn after drawing a white ball is

Similarly, we have

Since

and,

based on the Bayes’ decision rule, the above decisions stand.

Combined decision:

In this situation, from a combined point of view, the observations of the decisions of the participants are the same as the observations of the colors of the balls that the participants draw. Thus, conditioned on the type of urns, $D_n, n=1,2,3,\ldots,N$ follows IID Bernoulli distribution, and we have,

and,

Let $n_A$ be the number of decisions from the participants that choose A, then $n_A$ is a random variable, and it follows Binomial distribution conditioned on the type of urns:

From the Bayes’ Theorem, we get the posterior Probabilities,

According to the Bayes’ decision rule, if , or equivalently, $n_A>\frac{N}{2}$, we decide $A$, because , and vice versa for urn $B$. In conclusion, the combined decision rule is a simple counting heuristic, if more participants decide urn $A$ than urn $B$, we choose urn $A$ as the combined decision, and vice versa. If equal number of participants decide urn A and urn $B$, this is inconclusive and we can decide either of the two.

Scenario II:

Things begin to get tricky in this scenario, since each participant knows her predecessors’ decisions. The first participant, her only information is her own draw. She will predict $A$ if she draws a black ball and will predict $B$ if she draws a white one. So her decision reflects her draw. If the second participant’s draw match the color of the first person’s decision, then the second participant should make the same decision as of the first participant. However, suppose the other way, the first participant draws a black and predict $A$ and the second participant draws a white. According to the Bayes’ Theorem, because the urn sample is balanced, with equal probabilities $\frac{1}{2}$ of the priors of the type of the urn, the posterior probabilities are .

Tie breaking:

Based on the Bayes’ decision rule, this is inconclusive, and we can choose from two schemes to break the tie, the first scheme is that the second participant will choose the type of urn that matches the color of her own draw; the second scheme is to make the decision randomly, that is the she decides either urn with probability $\frac{1}{2}$. Here, we will choose the first scheme, one of the reasons is that, in real life, the first person can make an error (draw a white and predicts $A$), and this scheme will cancel out the effect of the error. Essentially, the two scheme are the same, with only some numerical probability calculation differences.

Cascade formation:

Suppose the first two decisions are $A$, and the third participant observes a white ball, then this participant is deciding on an inferred observations of two black draws and her own white draw. Since $A$ and $B$ are equally likely a priori, and since the sample favors A, the posterior probability of A is strictly greater than $\frac{1}{2}$. Following the Bayes’ decision rule, the third participant should decide urn A in spite of her own draw. Hence, the first two agreed decisions start a cascade in which the third and later participants will ignore their own draws and follow the agreed decision. It is worth mention that, the cascade can start at any position after the first two participants.

Individual decision:

Generally, let $n_A$ be the number of black balls that the $n$th participant infers from her predecessors; let $n_B=n-1-n_A$ be the number of white balls that the $n$th participant infers from her predecessors. The posterior probabilities are

The optimal decision process for each participant is the following:

- If $d=n_A-n_B\geq2$, no matter of which color the $n$th participant observe, she has , so she should decide A.

- If $d=n_A-n_B=1$, if the $n$th participant draws a black, then , she should decide A; if the $n$th participant draws a white, then , she should decide B, based on the scheme we set up.

- If $d=n_A-n_B=0$, if the $n$th participant draws a black, then , she should decide A; if the $n$th participant draws a white, then , she should decide B.

- If $d=n_A-n_B=-1$, if the $n$th participant draws a white, then , she should decide B; if the $n$th participant draws a black, then , she should decide A, based on the scheme we set up.

- If $d=n_A-n_B\leq-2$, no matter of which color the $n$th participant observe, she has , so she should decide B.

Combined decision:

Regardless of the sequence of decisions of selections, with the decision of all $N$ participants observed, the posterior probability of $A$ is

Similarly,

Just like Scenario I, the combined decision rule is again a simple counting heuristic, if more participants decide urn A than urn B, we choose urn A as the combined decision, and vice versa. If equal number of participants decide urn A and urn B, this is inconclusive and we can decide either of the two.

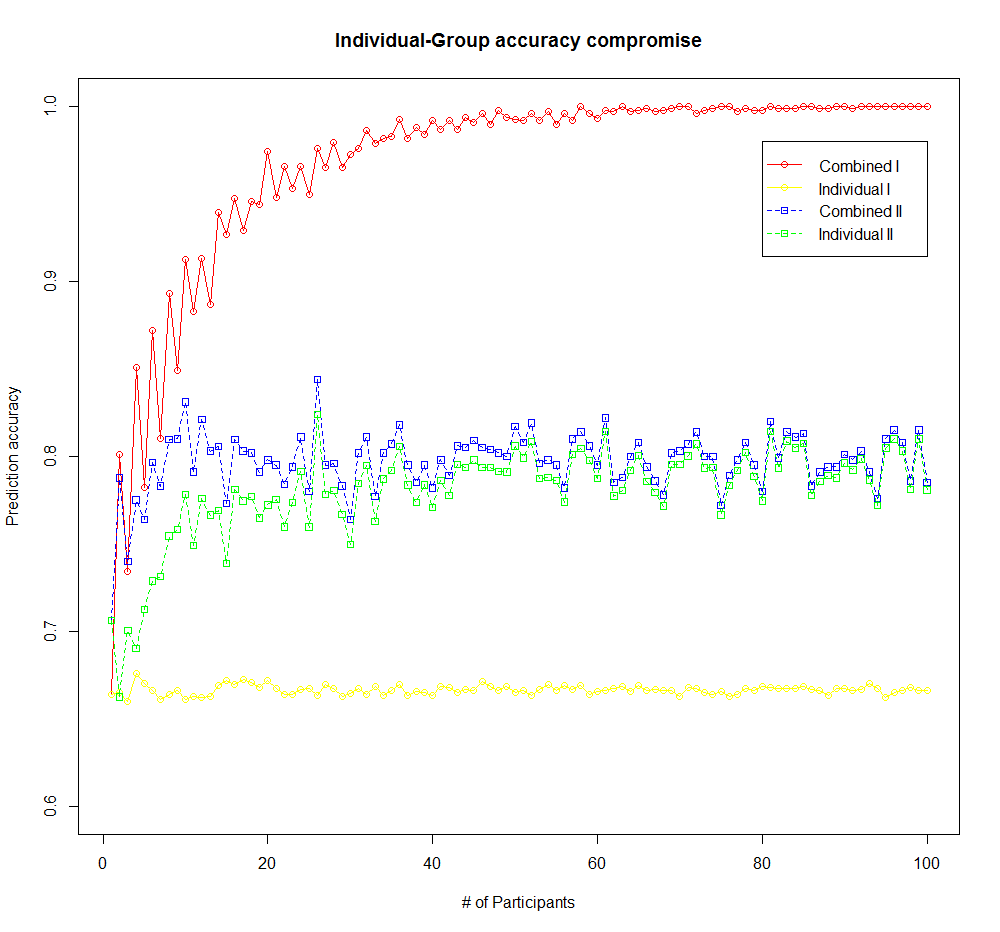

Comparison and simulations:

The following simulation has experiments with number of participants ranging from 1 to 100. For each experiment, we have 1000 repeated trials, and we take the average of the correct prediction rates of the 1000 trials, for both individuals and combined, as the prediction accuracy from scenario I and II. Since this model is balanced, with equal probability of choosing urn $A$ and urn $B$, and the probability of selecting a black ball from urn $A$ is the same as the probability of drawing a white ball from urn $B$. So, without loss of generality, we set the urn predetermined to be urn $A$. Then, any participant, no matter which color of ball she draws, who decides urn $A$ would be considered as making a correct prediction, on the other hand, who decides urn $B$ would be considered as making a wrong prediction.

Which is shown in the screenshot below and also this link for R code: